La Réunion is growing. I mean actually GROWING, not just demographically, metaphorically or musically but literally, physically, putting on the inches. The Piton de la Fournaise, a volcano situated at the island’s southeastern tip, erupts a few times a year – ‘in the Hawaiian style’ according to Wikipedia – sending floes of lava down its steep eastern flanks towards the main Nationale 2 highway. Sometimes the Piton gets really mad and its red hot ejaculations ooze further than usual, destroying parts of the road and tumbling into the sea beyond in great big belly-flops of steam and fire. The lava then solidifies adding new land to the total surface area of the island.

When I ask Danyel Waro whether he attaches any symbolic meaning to this fiery expansion he gives me a shy, slightly nervous sidelong smile, unsure whether I’m being entirely serious and answers, “Ahh, well. Yes, in a way. The lava makes the country grow and its image is growing too. But its geology is extraordinary. Really superb.”

Waro should know. The smallholding in the rural community of Le Tampon where he was born, raised and still lives is no more than fifteen miles due west of Le Piton’s smoking crater. He came into the world with russety straw-coloured hair, a coco rouge in local Creole parlance, and island lore has it that the redheads of La Réunion’s uplands have hair tainted by volcanic lava. But above all, there’s no one alive who’s done more to expand the reputation of La Réunion and put this small clod of lush green vegetation and soaring volcanic peaks on the musical map.

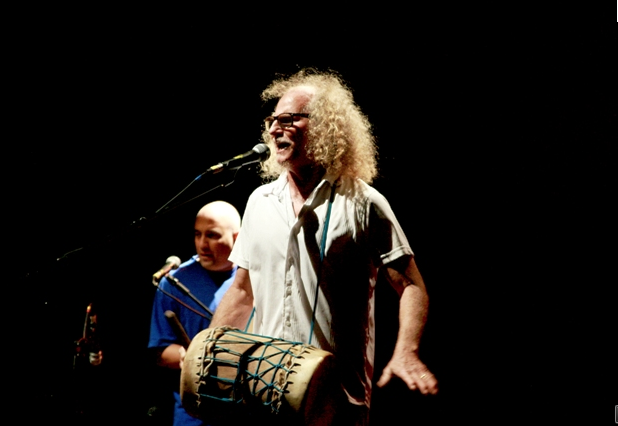

Fans the world over venerate the passion of Waro’s performances and the spiritual, almost sacred intensity of his music; its raw simplicity, trance-inducing power and wild rhythmic joy. Those who can speak Creole, or maybe just French at a pinch, also attest to his sublime skills as a poet, storyteller, philosopher and social commentator. To many Réunionnais he is simply an island hero, a local boy from the wrong side of the tracks made good on a global scale, a musical champion who for over thirty years has fought their fight for the right to be different, to be proud of their unique mongrel culture, to be happy with who they are. And when he squirms apologetically every time such accolades are heaped, they love him even more.

Despite having half a dozen acclaimed albums to his name, a clutch of gongs including the 2010 Womex Artist Award and an Academie Charles Cros “Coup de Coeur”, alongside decades of touring in mainland Europe and beyond, Waro had never visited the UK until last summer. His afternoon workshop at the WOMAD Festival in Charlton Park may have been slightly less intense than the full blown show he was to give on the main stage later the same evening, which for those lucky enough to see it, was one of the highlights of the Festival. But it was enthralling nonetheless. When it had finished, I sat awkwardly in the back stage tent while Waro stripped off his sweat-drenched t-shirt and prepared himself, with quick considerate movements, to answer my questions. It was the fourth and final installment of an interview that had been in progress, off an on, since April.

Our very first meeting took place in a hotel lobby on the left bank of the Seine in Paris. I had noted the time of our meeting incorrectly on my scrawny Parisian diary sheet and was consequently an hour late for the interview, a mistake that would have caused a reaction of glum annoyance, even anger, in most other busy artists. Understandably so. Waro however didn’t show even a hint of short temper, treating my misdemeanor with the insignificance it deserved in the great scheme of things. After my profuse apologies, we made small talk, mostly about his recent trip to India. Very quickly enthusiasm warmed up his answers as he talked about his meetings with Tamils, and his desire to get to know Tamil culture better in view of its importance in the cultural weave of his island home.

Out in warm spring sunshine on the Left Bank, Notre Dame glowing like a honeycomb ahead of us, I was able to take the measure of the man. His physical presence was engagingly eccentric; small, thin and wiry with puffs of chaff-red and white hair bursting out from under his black bobble hat and sprouting like wise brillo from his chin, cheeks and ears. His face had an elfin shape that jutted into a strong and definite V at the point of his bushy chin. He wore a pair of extra thick ‘national health’ glasses, behind which two warm and constantly moving eyes swam like brown pebbles in an animated stream of curiosity and enthusiasm. He had the frame and manner of a workman, a person well used to digging the earth and chopping wood, not one to make a drama out of physical labour.

From the start, I liked his lack of dogma. When I remarked on the irony that it was a priest who introduced the first black slave into La Réunion at the end of the 17th century, Waro was quick to say that there were many priests who rejected the Catholic power and its shameful endorsement of the whole system of slavery. His vision seemed to be unclouded by feelings of hatred or vengeance. As we walked towards the metro, Waro’s answers to my questions were long, detailed and generous. I apologised once again for my shambolic timekeeping and he just apologised back. “Don’t worry,” he said, “I like talking about these things. In fact, I’m sorry if I talk too much.”

Down in the clanking growling depths of the RER, Waro told me a legend about the Piton de la Fournaise. “In the old days,” he said, “there was a woman, a slave trader, who owned a huge estate near St Paul. Her name was Madame Desbassayns. Some people see her as a very good person, but that’s the Catholic view. For others, she was the devil. There are those who believe that she’s still living inside the volcano, in that hell. From time to time she wakes up, and the volcano erupts.”

Before Madame Desbassayns and her kind turned La Réunion into yet another colonial slave economy producing natural ‘highs’ like sugar, coffee and spices to satisfy European cravings, it was just an empty fertile volcanic slab in the Indian Ocean, thirty miles long by twenty wide, about 120 miles east of Madagascar and 6,500 miles distant from France. The first settlers arrived in the decades after 1642 when the island was claimed by the Kind of France as his personal possession and renamed Île Bourbon. They were French adventurers, fearless and resilient men from Brittany and Picardie; soldiers, carpenters, masons, surgeons, chancers, sometimes even renegades or bandits on the run from the law. Among them was a Monsieur René Hoareau from Meneville in Picardie, the ancestor of the many Hoareaus or Waros who now inhabit the island.

Some of these first migrants of fortune married black Malgache women, not slaves but free women of African birth, from the French trading post at Fort Dauphin in Madagascar. Danyel Waro takes pains to underline this fact to me. “They were free spirits,” he repeats, with eager emphasis. “Pioneering women. It was a new society, before the real beginnings of slavery. There was this first intermingling of Indian, Malgache and French that lasted about thirty years, and then slavery arrived with the Compagnie des Indes (The French East India Company) and there was a new workforce, mostly African and Malgache. The first 500 Réunionnais are well known, their names, which boats they arrived on, everything. Then afterwards, the slaves just arrived in the form of loads, like animals, and they were nameless.”

The essential bastard nature of La Reunion is something that Waro endorses with insistent zeal throughout our various conversations. The island is without doubt a miniature rainbow ‘nation’ with a scrabble-ready collection of richly hued Creole words to describe its various ‘tribes’; kaf (black African, from Arabic kafir meaning ‘unbeliever’), Malbar (anyone of central Asian descent, after the Malbar coast, where the first Indian arrivals on the island came from), yab or ti blan (small time poor white farmer), Malgache (anyone from Madagascar), Komor (anyone from the Comoros), Sinwa (Chinese), Zarabe (Arab or Muslim) and Zoreil (wealthier French landowning or administrative class). The fact that all these ethnic groups coexist on their tiny island in relative peace, each with their own faiths, rituals, feast days, music and food, at times separate, at times combining and mingling, is astonishing. It reveals a shared sense of belonging and destiny that Danyel Waro holds in deep affection and praises in his music time and again.

In fact, he’s turned it into a kind of creed, which he calls batarsité, (lit. ‘bastardy’) which also happens to be the name of one his most popular albums, released in 1994. A full-length documentary about Waro’s life released in 2008 and directed by Thierry Hoareau, a relation of some kind no doubt, is entitled Fier Bâtard or ‘Proud Bastard’.

When I ask Waro about racism in La Réunion he’s ready with his answer: “Our reality is deeply mixed but the conscience doesn’t always follow that. Up in the head there’s always that desire to be pure, pure white maybe, but pure Indian or pure black as well. That’s why I talk about batarsité. It’s my way of saying let’s look at ourselves, in the mirror, look at what we desire. We’re just as mixed in our blood as we are in our culture, despite appearances. I always say that I’m made up of Indianité, kaffitude, Malgachitude, all of that. Whether I like it or not, it’s already done inside me.”

I can’t help feeling however that there’s something else behind Waro’s words, a more personal struggle, and it has to do with the fact that he has adopted what was originally a black African form of music as his own, a music spiced with Asian flavours – mizik kaf i malbar to use the local parlance – that was despised and hidden away in the recesses of La Reunion’s conscience like something wicked and shameful right up until the late 1960s. Then it was ‘discovered’ by a whole generation of young Réunionnais musicians and artists, both white and black, who turned it into the soundtrack of their struggle for autonomy and independence. So in effect, like the Rolling Stones, Elvis Presley and Eminem, Waro has taken a style of music that wasn’t his by birthright and fashioned it into something new. But Waro’s whole point is that, thanks to the island’s unique blurring of racial and cultural dividing line, this music is in fact his own. It is his birthright as a Réunionnais and a ‘proud bastard’. The music in question is maloya.

Waro never heard any maloya until he was eighteen. He was born in 1955 in a country shack with three acres but no electricity or running water, about 600 metres above the seaside town of St Pierre, with wide commanding views of fields, volcanoes and the distant sea. This was land that had been given to poor white farmers many decades before to remove them from the more fertile regions below, which the powerful landowning classes claimed for themselves. Apart from a desire to grab all the best agricultural soil, those same landowners feared the hostility of any potential alliance between poor white farmers and the poor blacks or Indians who provided the bulk of the labour on the big plantations. It was deemed prudent to send the yabs up-country and thereby avoid hope of solidarity among the oppressed.

Waro’s father had no time for music, poetry or any frivolities of that nature. “He grew up in austerity and obscurity,” says Waro. “He had a really difficult childhood and that gave him this rigorous mentality. But it was apt as well. We couldn’t just hang around. We ate what we grew; maize, pulses, beans, potatoes and all kinds of root vegetables, which we also fed to the pigs and chicken. And all that doesn’t grow by itself. So every day, before and after school we cut cane, tilled, hoed, weeded. It was all about rigour, and that rigour has given me many things. So I don’t complain.”

I try and imagine Waro’s childhood in the soil and dust, the crystalline air and unrelenting heat of the high Réunionnais plains and a kind rural epic, a cross between Steinbeck, Faulkner and The Waltons, set in the Indian Ocean, comes onto my mental screen. No doubt the truth was more mundane, and more exotic still.

“Our house was cramped,” Waro remembers, “and I shared my bed with my four brothers, but I had acres of fields to run around in to, so it wasn’t too bad.” He suffered from diphtheria, which was often fatal at that time, and his mother vowed to the Virgin Mary to dress him in white and blue for five years if She would just spare his life. “By their faith, their love, their healing, my mother and godmother cleaned out my throat and saved me,” he later told the French journalist François Bensignor. “So I’m a bit miraculous. And now my throat dictates my existence. That’s the miracle!”

Waro has hinted in interviews that his father occasionally drank too much rum and became abusive to his wife and children. This is probably the source of Waro’s lifelong aversion to alcohol, cigarettes and marijuana, all of which are party staples on the island. He assures me that both he and his group are entirely ‘clean’ in that sense.

“Maloya has so often been lumped together with a bottle of rum, but that association doesn’t interest me,” he says with conviction. “It’s one of the reasons why the music was just chucked in a sack in the past, like a piece of garbage belonging only to the poorest, or stupidest, or blackest. If you love what I sing, you don’t have to drink to appreciate it. That’s what I say.” It should be added that despite everything, the memory of his father inspires great love and respect in him now. “I owe him more than one song,” he says with tenderness.

Waro sang in the fields and listened to the Creole tales and riddles told by friends and neighbours. It was a fecund trove of language, which the absence of radio and TV only made richer and more vital. He also listened to the political views of his father, who was a staunch communist and supporter of the Parti Communiste Réunionnais, or PCR, which was founded in 1959 by the visionary Paul Vergès. “I grew up with politics,” Waro says. “And with the communist and autonomist parties that were more or less forbidden then. I spent my youth in a climate of resistance.” Later, as a teenager, Waro organised strikes at his Lycée.

Music was only a distant presence in the house. There was a radio, but it was only there for the news. Nonetheless, Waro felt the magnetism of the Tamil drums, the Creole songs and the whole kaleidoscope of the island’s musical life that went on around him, undervalued by most.

When his adolescent hormones started to kick in, he listened spellbound to his sister’s 78s of Georges Brassens, the French balladeer. “I remember I would listen to the same songs over and over again, copying out the lyrics and doing everything to enter his world, which was a little anarchic but sensual at the same time,” says Waro. “To hear him talk about women, about sex too, with that kind of non-misogynistic misogyny, that interested me greatly.”

Brassens was the big influence in Waro’s formative years, and apart from the island sounds all round, Brassens is still number one for him. “I’ve never listened to much music except Brassens. I’m not a great music listener, nor an avid reader. I don’t want to be greedy and listen, listen, listen. That’s a kind of pollution. I just want to take things in small doses, what I like, when I Iike, and make my own sauce from it.”

In 1973, at the annual Festival of the Communist Party, known as the Fête Temoignage, where the eighteen year old Waro was working as a young volunteer, he saw a performance by Firmin Viry, one of the gran moun, or ‘great people’ of maloya. The experience changed his life forever.

They say that the word maloya comes from the Malgache maloy aho, which means something like ’speaking your heart’ or ‘telling your truth’.It also means ‘great sorcerer’ in Zimbabwe or ‘incantation’ and ‘sorcery’ in Mozambique. In other words, it’s always been a very potent word. And now it also describes a music originally played by the black underclass of La Réunion, most often to accompany ancestor-worshiping rituals called servis kabaré which lasted all night or even several days.With its huge pounding roulèr drums of wood and beef hide, its clattering pikèr bamboo percussion, its shuffling kayamb or wooden ‘tray’ of cane stalks, its zinging bob or one-stringed arc and gourd, and its keening, yearning call and response vocals, maloya was designed to invoked a state of trance in devotees, powerful enough to draw the spirit of the ancestors out of obscurity and into the here and now. According to the late Granmoun Lélé, another true original of the genre, those spirits have the power to grant their descendants a state of grace, to lighten their paths and their loads, to heal their sorrows and their broken bodies. But in order for those ancestors to come, the maloya has to be sung with total sincerity and abandon, from the bottom of the singer’s heart. Anything less, and the departed gran moun will just stay in heaven.

Like American gospel, Brazilian candomblé, Cuban santéria, Moroccan gnawa and Jamaican nyabhingi, maloya was originally a method of inducing well-being, joy and a sense of power through solidarity among the living, and between the living and the dead, whose spirits dance in the tropical night air. Its devotees were the descendants of slaves, a people who had been robbed of everything apart from their life on earth, their memory and their culture. And like all those other ‘African’ systems of belief and transcendence, maloya is a mongrel phenomenon. The original ancestor-worship ritual was supposedly imported from Madagascar, but it has since been nourished with music and ritual from India and other parts of Africa. Granmoun Lélé himself was an incarnation of these hybrid genetics. His mother was kaf, with Somali, Comorian, Malgache and Zanzibari blood pulsing through her veins. She was baptised a Christian, and so was her son. His father was a malbar, a Hindu with roots in Tamil Nadu. He was a sculptor by trade whose job it was to renovate and maintain the masks and statuettes used in the Bal Tamoul, the sacred ritual theatre of the Tamil people which replayed scenes from the Ramayama epics.

When the PCR first started to programme Firmin Viry and his family troupe at political gatherings in the late 1960s, maloya was still a proscribed form of music, hidden away in the black shanty towns and worker’s quarters, reviled by the ruling French elite, who only tolerated its more romantic and quaintly folkloric cousin sega, another musical casserole in which African elements are mixed with the genteel quadrilles of the slave owning classes and the popular music of France and Europe.

Maloya was uncompromisingly black and possession of a roulèr or kayamb could earn you a stint in jail or maybe even a few lashes of the sabouk or slave-owner’s whip. The noise of the all night servis kabarés was deemed intolerable, a public nuisance of the worse kind, by priests and ‘quality’ folk alike. According to the likes of Michel Debré, French minister for overseas territories from 1960 to 1983, and a passionate supporter of Christian values and assimilation with France, maloya was only a vulgar reminder of slavery and the shame in La Réunion’s history. Moreover it was sung in Creole, an “absurd” folk language, which the elite deemed incapable of expressing deep emotions or civilised opinions. For them, maloya was best forgotten.

But that past and that language were precisely what the PCR and its supporters wanted to bring out into the open and unfurl. Their heroes were the maroons or slaves who escaped to the high hills and plains of La Réunion to find freedom from the brutality of the slave owners. In the raw, unadorned lyrics of songs by Firmin Viry and Granmoun Lélé, they heard the whispers of that old renegade defiance, a cry of freedom, sung in Creole and rooted in a distant past that, far from being shameful, actually defined the real soul of La Réunion. Maloya was co-opted by the communists as a cultural insignia and a political weapon against old prejudice.

To the young Waro, Firmin Viry was a revelation. “I was standing next to Viry and his family when he was getting his roulèr ready, heating up his skins, getting ready to go on stage,” he remembers. “Seeing them play provoked a physical reaction in me. I immediately wanted to take that music into my heart and soul. After that I met and saw other singers like Granmoun Lélé or Le Rwa Kaf who became very important to me, but Firmin Viry is my model, that’s for sure.” If you want to know where Waro’s pared down and pulsing style comes from, listen to Firmin Viry and Granmoun Lélé.

Waro fell in love with maloya and all that it stood for. When I ask him to explain what the genre means him to him, to give me the non-ethnomusicological definition, his answer is redolent of that love. “It’s a philosophy. It’s a way of being. For me, maloya is the flower that was absent in my youth, the tenderness that I missed, the love that I needed. But it’s also resistance, defiance, because maloya’s African soul reached out and touched everything that was suppressed and forbidden and allowed it to feel whole, to harmonise itself.”

Waro joined Viry’s troupe on an occasional basis before putting together his own band of fellow agricultural workers. The first recorded gig under his own name was on December 27th 1975. Waro was twenty years old. He’d just failed his baccalaureate. He was young, confused and maloya mad. The following year he was shipped over to France to do his military service, knowing all along that there was no way he would ever don a uniform, shoulder a gun and salute the tricouleur. When he arrived in the ‘motherland’ he refused to join up and his defiant pacifism earned him a 22-month stint in the Centre de Détention d’Écouvres in Rennes.

Prison was a refuge, a space to reflect and seek answers to the questions blue-bottling in his mind. Waro spent his time writing poems, sending letters home and composing songs. One of them ‘Degaz Anou Vitnam’ (‘Get Out of Vietnam!’) appeared on his 2010 release Aou Amwin, a double CD of great invention and originality, which many consider to be Waro’s masterpiece. He also managed to pen a novel entitled Romans ékri dan la zol en frans (‘Novel written in gaol in France’), which was published on his release in 1978, with drawings by Kaniki. It has been described as a kind of extended maloya poem, in which Waro rails against the enemies of independent Réunion, especially the despised Michel Debré. “Maloya nourished me during those years of prison,” he later told the Swiss journalist Elizabeth Stoudmann. “I had just discovered it when I was sent to Rennes. I didn’t sing inside, but I wrote a lot. I realised that I didn’t know La Réunion that well. I accepted prison as a retreat. I took stock.”

When Waro returned to Réunion in 1978, revolution was in the air. A whole new generation were proclaiming their Réunionnité and the need to break with the old colonial mindset. Writers and poets such as Boris Gamaleya, Anne Cheynet, Alain Lorraine, Georges Gauvin, Axel Gauvin and Carpanin Marimoutou, some who were staunchly communist, others wary of established political creeds, were forging a new Creole voice, pushing the once oral language into the domain of literature and written discourse. They saw their struggle paralleled in other parts of the old French Empire, especially the other Creole speaking islands of Martinique and Guadeloupe, or parts of France such as Brittany or Occitania in Provence, where minority tongues that had once been smothered by the might of the language of Moliere were also undergoing a renaissance.

Musicians like Alain Peters, the doomed junkie hero of the new electrified ‘rock’ Maloya and groups such as Ziskakan, Baster, Sabouk, Ti Fock and Persée Poliss were starting to inject the old maloya of Firmin Viry, Granmoun Lélé and le Rwa Kaf with a new uncompromising zeal, a youthful taste for confrontation and revolt. Some veterans, like Viry himself, were shocked at the brash rock and reggae tones that began to be added to what had long been the relatively unchanging acoustic roots sound of maloya. To him, such new hybrids might be music, but they weren’t maloya.

Danyel Waro may not have been shocked, but he showed little sign of wanting to be a musical iconoclast. On his return home he started to make traditional maloya instruments for a living. There was huge demand for good roulèr drums, bobs and kayambs because most of these instruments had been confiscated during the previous decades. “I’ve been familiar with the kayamb since early childhood,” he told Elisabeth Stoudmann. “But in pieces. I come from the earth, from sugar cane, and I went back to the earth and sugar cane thanks to musical instruments.”

Waro also continued performing with his troupe and started frequenting various kabar ceremonies, dousing himself in their raw intensity and spectacle. He became a familiar figure at the kabar held by an old maloyèr called Granmoun Baba, eventually becoming part of his extended ‘family’ of musicians and friends. “His wife Madame Baba still carries on,” he tells me. “She’s 92 now and she performs the ceremony every year.”

Danyel Waro was now approaching his quarter century and experiencing important shifts in his political and creative philosophies. He was beginning to loose his taste for the rigid certainties of communism, with its central control, its dogmatic rationalism, its distrust of individualism and its veneration of great leader figures like Marx, Lenin and Mao.

“The idea of communism or socialism as a philosophy of sharing and social justice has remained with me,” he explains. “And I’m still against the capitalist profit motive because that’s where injustice, domination, abuse and lack of liberty stem from. But I’m also against the hoarding of power, against centralism. The problem with communism is that it claims to possess the truth because it has a good idea. That idea is equality, justice and wellbeing for all, and you line-up obediently behind that idea, but it belongs to someone, to a person, to a few people. And lining up behind it you loose that personal liberty, which communism considers to be a bit of a bourgeois concept. If you’re against the top man, the great leader, you’re considered a kind of counter revolutionary. But I defend that freedom of expression, of seeking the truth.”

At the dawn of the 1980s, the island’s radical left was split into two camps; those who favoured autonomy but under the umbrella of the French nation (La Réunion had been a department of France since 1946, with the same supposed rights and privileges as any department of mainland France itself), and those who preferred a complete break with France and real independence. For the latter, being part of France meant being subjected to an enduring French colonialist mindset, whose only ultimate interests lay in destroying genuine Réunionnais culture and assimilating the island into the superior certainties of the French state, French culture and the Catholic faith. Waro was an indépendantiste, whereas the PCR favoured autonomy but fought shy of a complete break with France.

And so Waro left the purely political path of the committed activist, and forked off on his own artistic one. He reformed his troupe and started to perform regularly. In 1981, the election of President Mitterrand and France’s first left wing government in two generations changed much in La Réunion, as it did throughout France and its dominions, sweeping away old and narrow-minded cultural restrictions and empowering creativity of all kinds at all levels. Maloya shook off its last few fetters and emerged into the open, free at last. Kabars and concerts no longer had to be hidden away or officially sanctioned by the local prefecture. The maloya inspired music scene blossomed like a desert after a flash flood, as did many other local Creole art forms. Some have even called what happened a kind of Creole movida. “The renaissance of maloya gave back a worth to all that African part of ourselves that had been devalued and hidden for centuries,” Waro says. “We won back a piece of ourselves.”

Waro had decided he was a musician, not a politician, and his music was maloya. But his passions continued to intermingle. He re-entered politics in the late 1990s, as member of the candidate list of the Nasyon Réyoné Dobout (‘Reunion Nation Stand Up!’) Party. It won a meagre 0.77% of the island legislative elections in 1998. Perhaps even the most hardened Réunionnais nationalists had to admit that without subsidies from France and the European Union, life on the island would be even harder than it already was. Independence continues as a state of mind at best, albeit one that influences much of Waro’s creativity and philosophy to this day.

Meanwhile, Waro’s musical career developed in an eccentric fashion. His reputation at home and abroad grew steadily during the 1980s and 90s, eventually hoisting him up to the pinnacle of the new breed of maloya artists who started their careers in the late 1970s and early 1980s. And yet, by 1990, even though Waro was touring places like Japan, only one meagre cassette of his music was available in Réunion.

The fact is that Waro still saw himself as a militant, of a creative musical kind. He instinctively shunned the whole machinery of musical production, of labels and press attachés, of marketing and video clips. He took this attitude despite the fact that it was the PCR itself that had kick-started the phonographic production of maloya when it released a series of LPs and singles by the likes of Firmin Viry in the late 1970s and 1980s. But it wasn’t until Waro met Philippe Conrath, boss of Cobalt Records and the innovative artist-breaking Africolor festival in Paris, that he felt inclined to engage with the record industry. We must thank god and the ancestors that he did.

Meanwhile, the concert was Waro’s forum of choice and the only place where he felt a direct and meaningful relationship with his audience, without danger of distortion from third parties working for the profit motive. That is perhaps why his concerts are so intense, so driven, so immediate and vital.

I ask Waro where this intensity comes from. “It’s maloya,” he answers. “In the ritual, there’s this gradual crescendo of chants, and singing. Everyone is involved. Everyone is on the same level. There’s the soloist who starts the chant, there the instrumentalists behind him and then it progresses with chants and songs intensifying, the rhythm comes in, to make people dance, to give pleasure to the ancestors. For me it’s all of that.”

So are you trying to recreate the ritual, the servis kabaré?

“For me, when I’m in front of an audience, it’s all about trying to build something which kind of sacred, something powerful and deep. But then, I’m not trying to recreate the servis kabaré, no. When I compose my songs, and try to find the right words, I’m trying to create something that isn’t just partying for partying’s sake, or dancing for dancing’s sake. It’s something with meaning, I don’t know what meaning, but something that touches people and touches me. I don’t even sing for others. I try to feel good myself. I often say it’s like bewitching…like casting a spell on myself. I don’t always get there of course, but that’s how I see it.”

There’s little doubt that music is still a form of activism for Waro. That explosive spirit of defiance and renaissance that gave birth to the new maloya in the late 1970s still infuses his recordings and shows. But when I spoke to him at WOMAD this year, when he seemed more relaxed, more forthcoming and effusive than during our previous conversations, I felt I was listening to a man who has achieved a new stability and philosophical tranquillity in his life.

“The place where I’m at peace is at home in Le Tampon,” he tells me. “I have to feel calm to create, write a song, and find the right words. I take something from every place I visit, I take emotions when I’m walking, from the light, from nature. I go to La Chapelle to hear the drums. I’m a bit of sponge in that way. But at the same time, I don’t want to take too much.”

There’s always that emphasis on words when Waro speaks about his art. Finding the right words is his holy grail. And in fact, if you look at his career, it’s the words that have soaked up the larger part of his creative energy. The music has stayed pretty much the same at its core, despite innovative forages into other styles and collaborations with musicians from France, Corsica, Morocco and elsewhere. The harmonies on last year’s Aou Amwin are also lusher, more experimental than before, thanks apparently to the input of Waro’s son Sami Waro and others. But the heart of the sound is still pure roots maloya with roulèr, pikèr, kayamb, triangle providing the warmth, and the heat.

As a creator, Waro is essentially a word man (he also happens to be a powerful and nimble vocalist). But he’s also been venturing slowly into a more wordless territory of pure spirit, beyond ideas, discourse and the Cartesian rationalism (his phrase, not mine) of his youth. The Chapelle he refers to in the answer above is the renowned Chapelle de la Misère, the ‘Chapel of Misery’, which is situated in St Paul, not far from his home. It’s run by the inspirational Daniel Singaïny, once a communist like Waro, but now a hugely respected community leader and spiritual guide. The main strands in his ritual are Hindu and Tamil – fire walking and sacrifice to the goddess Kali are staples – and his temple is extremely popular with working class Réunionnais. Waro has been going there for about thirty years, but for most of that time his interest was musical, creative and cultural. Things have changed recently.

“I first did the fire walk a few years ago,” he tells me. “I had taken my time for many reasons, to do with my own feelings about ritual. I took that path little by little, going to La Chapelle de la Misère to learn about Tamil culture, to lend a hand during the ceremonies, to play music and help. But now I’ve taken a step that’s a little more important. I’ve gone more deeply into the ritual, into the spiritual and religious side in a real sense. It’s no longer just a cultural thing, an appreciation. Today I actually take part in the ceremonies, I do my observances, my fast.”

This new implication in the realm of pure spirit has lead Waro to a new place in his life, a place that is more earthed and grounded. “It’s been a long time that I’ve been sorting things out. I can see clearly what’s worth keeping or not keeping in the political life and all the pressure groups I used to be part of, with the autonomists, the nationalists, the different collectives who were fighting the fight. What’s bad in me needed to be cleaned in order for me to be myself and become non-violent and genuinely tolerant. I don’t want to be revolutionary just for the word ‘revolutionary’. What interest me now is to really be. And being myself is being Indian as much as white as much as kaf as much as Malgache. In the end, I’m all those things. It’s about freedom in every sense of the word. Freedom to plant your own seeds, to value the tree next to your house that gives you shade, or the jackfruit that feeds you. It’s finding what’s essential in life. It’s about taking responsibility for myself, laying claim to myself and then getting beyond that struggle to a place where there’s no need to do those things anymore. And there I feel at peace.”

Can a white country boy sing maloya? Ladies and gentleman, please welcome Danyel Waro.

Andy Morgan. (c) 2011

First published in fRoots Magazine, UK – October 2011.

1 comment for “DANYEL WARO – Mongrel and proud”